Showing posts with label diagnosis. Show all posts

Showing posts with label diagnosis. Show all posts

Thursday, May 9, 2013

Thursday, March 21, 2013

LUMINEX xMAP Technology in Parasite Diagnostics

Over the past few years nucleic acid based methods have

revolutionised parasite diagnostics in modern clinical microbiology

(CM) labs. Real-time PCR is really gaining a foothold in CM labs, but

despite the opportunity for plexing, mostly only up to 6 DNA targets

can be included in each assay (due to the number of available

channels).

LUMINEX xMAP technology used for detection of specific nucleic acids (Dunbar, 2006) bypasses this limit, and up to 100 DNA targets can be included in one single assay in a 96-well plate format. You can read about the technology here.

LUMINEX xMAP technology used for detection of specific nucleic acids (Dunbar, 2006) bypasses this limit, and up to 100 DNA targets can be included in one single assay in a 96-well plate format. You can read about the technology here.

Saturday, November 10, 2012

How Hard Can It Be?

How strange the world of clinical microbiology is when you compare the fields of mycology, parasitology, bacteriology and virology to each other. Such different possibilities, opportunities, limitations, and diagnostic challenges! The 3 month mortality rate of invasive aspergillosis, a disease mainly caused by Aspergillus fumigatus and seen in mainly patients with haematological malignancies, patients undergoing allogenic HSCT and patients in ICUs, may be as high as 60%, and therefore a quick and reliable diagnosis is mandatory to secure timely therapeutic intervention. But, - Aspergillus fumigatus happens to be ubiquitous, and contamination of patient samples, whether blood or airway samples, may always be a potential cause of false-positive test results, and one of the reasons why the use of PCR as a first line diagnostic tool in routine mycology labs is still limited. Antigen tests, such as the Galactomannan antigen test, which also allow quick diagnosis can also be false-positive, not only due to sample contamination, but also due to galactomannan residues in medical compounds, such as the widely applied antibiotic Tazocin (piperacillin-tazobactam), which means that patients who have been given this drug and who submit a blood sample for galactomannan testing may test slightly positive even in the absence of an Aspergillus infection.

These are only some classical examples. In the field of mycology, positive predictive values (PPV; i.e. what is the probability of disease given a positive test result) are sometimes unacceptably low, and the lower the prevalence of the disease, the lower the PPV. This means that you need a lot of experience and knowledge on pre-test-probability + data from clinical and diagnostic work-ups, including anamnestic details, to determine whether or not the patient should receive therapy, such as treatment with voriconazole, - a relatively expensive drug.

|

| Aspergillus fumigatus - the most common cause of invasive aspergillosis - on blood agar. |

In the parasitology lab, however, things are quite different. Contamination of patient samples is rarely an issue, and in most cases not possible at all (disregarding DNA contamination of course). Specificity of microscopy is very often very high (close to 100%), which means that the PPV is very high even in cases where the disease is rare. Hence, if cysts of Giardia have been detected in your stool, it's due to the presence of the parasite in your body. It's a bit more tricky with PCR-based analyses, where the specificity does not rely on your ability to visually distinguish between e.g. Giardia and non-Giardia elements, but where it's all about designing oligos that anneal only to Giardia-DNA.

While in the mycology lab we struggle with low PPVs, one of the biggest challenges for me and my colleagues in the parasitology lab is to optimise the negative predictive value (NPV) of a faecal parasite diagnostic work-up - how can we rule out parasitic disease by cost-effectively putting together a panel of as few tests as possible?

There are many other differences. For instance, you can grow bacteria and fungi in the lab very easily, in fact, culture of bacteria and fungi is an essential diagnostic tool, which also allows you to submit the strain to antibiotic or antimycotic susceptibility testing and molecular characterisation/MALDI-TOF analysis in case you are not sure about the species ID. So, you have the strains right there in front of you, on agar plates, and they grow and grow, and you can keep them for as long as you like, - clean, non-contaminated strains on selective media.

You can't really do that with parasites, not nearly to the same extent and as easily, that is. For instance, you can culture Blastocystis directly from stool for sure (go here for the protocol), but only in the presence of bacteria (some of my colleagues do actually now and then manage to grow strains of Blastocystis in the absence of bacteria, they obtain what is called "axenic" cultures, but I believe that they cannot do it consistently and in limited time.). And it's a pity, since there is so much you can do when you have "clean" patient strains. Apart from susceptibility testing (which would actually be a bit difficult since Blastocystis is strictly anaerobic, so you can't really have it in microtiter plates or on RPMI plates on the table in front of you, but the strains could be challenged in the growth tubes), you can also extract DNA, and you would know that all the DNA that you extract from the isolate is from that particular strain, and not from bacterial contaminants. You can use the strain for production of antigens which can be used in ELISAs and used to generate mono- and polyclonal antibodies... Sequencing genomes of various subtypes would be a lot easier and quicker, and so on...

So, what appears obvious in one field of microbiology is not as obvious in another field, and vice versa. I wish Blastocystis was much easier to isolate. Dientamoeba too. Dientamoeba is probably as common as Blastocystis, and not rarely seen in co-infections. It is strange to contemplate that a parasite infecting hundreds of millions of people has not yet had its genome sequenced? We have no clue when it comes to effector proteins in Dientamoeba, and also for this parasite, what we know about its clinical significance relies mainly on epidemiological data.

There is no doubt that concerted efforts of experienced scientists should make it possible to develop appropriate and relevant culture protocols for these parasites. It does, however, require a lot of resources and time to get to know these common, but oh so fragile and reclusive little creatures...

Further reading:

Verweij PE, Kema GH, Zwaan B, & Melchers WJ (2012). Triazole fungicides and the selection of resistance to medical triazoles in the opportunistic mould Aspergillus fumigatus. Pest management science PMID: 23109245

Stensvold, C., Jørgensen, L., & Arendrup, M. (2012). Azole-Resistant Invasive Aspergillosis: Relationship to Agriculture Current Fungal Infection Reports, 6 (3), 178-191 DOI: 10.1007/s12281-012-0097-7

Maertens J, Theunissen K, Verhoef G, & Van Eldere J (2004). False-positive Aspergillus galactomannan antigen test results. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, 39 (2), 289-90 PMID: 15307045

Monday, October 8, 2012

Additional Comments on Blastocystis Treatment

I want to thank for the many emails I get! Unfortunately, I

cannot respond to each one of them, in part due to time limits, in part since some

of them are a bit off my topic or very difficult to answer. However, a few words on Blastocystis

treatment (again!), which will hopefully satisfy some of the readers:

Differences in the reported efficacy (microbiological and

clinical cure) of certain drugs or drug combinations may be due to one or more

of the following:

1) Actual differences in efficacy due to differences in pharmacokinetics,

and -dynamics. Some drugs used for treatment of intestinal parasites are

absorbed quickly from the intestine, while others are practically not absorbed

at all (but stay in the intestinal lumen). For instance: Metronidazole is absorbed almost 100% in the proximal part of the intestine and may very well fail to reach Blastocystis, which resides is in the large intestine.

2) Different methods are used for evaluating treatment

efficacy. If insensitive methods are used, the efficacy of any drug will be

overestimated. Culture in combination with PCR is clearly advantageous in terms

of evaluating microbiological efficacy since it will detect viable cells (see previous blog posts).

3) Drugs used in Blastocystis

treatment may have broad spectrum antibiotic activity (e.g. metronidazole) and

thus affect the surrounding microbiota, which again may influence the ability

of Blastocystis to continue

establishment. Hence indirect drug actions may play a role too.

| Could vegetables contribute to Blastocystis transmission? |

4) Diet. What types of food do we eat? I notice that some people

undergoing treatment for “blastocystosis” are cautious about eating carbs, for

instance, and turn to vegetables only or at least non-carb diets, thinking that

by cutting out carbs, they will cut off the "power supply" to Blastocystis. I’m not sure that this

approach is very effective and it’s also important to acknowledge that the

processing and metabolism of the foods that we ingest are complex. I hope to be able to do a blog post once on short-chain fatty acids, for instance. Again, changes in

our diets may influence our bacterial flora which again may have an impact on Blastocystis.

Importantly, we don’t know much about potential transmission of Blastocystis from raw vegetables and

whether this could be a potential source infection (vegetables contaminated

with Blastocystis).

5) Which leads to the next issue: The issue of re-infection. With so many people infected by Blastocystis (probably between 1-2 b people) it is likely that many of us are often exposed to the parasite. If we receive treatment but are not cut off from the source of infection, microbiological and clinical cure will be short-lived if at all possible.

5) Which leads to the next issue: The issue of re-infection. With so many people infected by Blastocystis (probably between 1-2 b people) it is likely that many of us are often exposed to the parasite. If we receive treatment but are not cut off from the source of infection, microbiological and clinical cure will be short-lived if at all possible.

6) Compliance - some drugs have serious adverse effects, and

so, failure to reach microbiological cure may stem from failure to comply with

drug prescriptions.

7) Differences in drug susceptibility. There is evidence from in vitro studies that Blastocystis subtypes exhibit differences in drug susceptibility.

7) Differences in drug susceptibility. There is evidence from in vitro studies that Blastocystis subtypes exhibit differences in drug susceptibility.

In the absence of sound data that take all of the above factors into account, it is not possible for me (or anyone) to predict exactly which drug (combo) that will work and which will not. I think that it is important that GPs or specialists who take an interest in treating Blastocystis collaborate with diagnostic labs that are experts on Blastocystis diagnostics. If any drug or drug combo enabling microbiological cure can be identified, such pilot data can be used to design randomised controlled treatment studies that again will assist us in identifying whether Blastocystis eradication leads to clinical improvement.

I will try and provide some thougths on other future directions for Blastocystis research soon. Stay tuned!

I will try and provide some thougths on other future directions for Blastocystis research soon. Stay tuned!

Tuesday, July 10, 2012

Blastocystis Culture in Jones' Medium

Upon request I have now posted the protocol on one of the simplest media used for Blastocystis culture, Jones' Medium, - please go to the tab (page) "Lab Stuff".

You can read about Blastocystis culture in some of my other blog posts, use the search box or the labels feature.

Please be aware that this is for xenic culture only - i.e. culture in the presence of bacteria. It's quick, inexpensive, very reliable (at least for human samples) and isolates can be kept this way for months/years - all you need is an incubator.

Extracting DNA from cultures and using it for subtyping usually yields excellent results.

I have never tried to cryopreserve (freeze down) Blastocystis using Jones' Medium, but it is possible (at least when Robinson's Medium is used).

More reading:

Stensvold CR, Arendrup MC, Jespersgaard C, Mølbak K, & Nielsen HV (2007). Detecting Blastocystis using parasitologic and DNA-based methods: a comparative study. Diagnostic microbiology and infectious disease, 59 (3), 303-7 PMID: 17913433You can read about Blastocystis culture in some of my other blog posts, use the search box or the labels feature.

Please be aware that this is for xenic culture only - i.e. culture in the presence of bacteria. It's quick, inexpensive, very reliable (at least for human samples) and isolates can be kept this way for months/years - all you need is an incubator.

Extracting DNA from cultures and using it for subtyping usually yields excellent results.

I have never tried to cryopreserve (freeze down) Blastocystis using Jones' Medium, but it is possible (at least when Robinson's Medium is used).

More reading:

And, if you are interested in culture of intestinal protists in general, why not look up

Sunday, July 1, 2012

Do I Get Diagnosed Correctly?

I can tell especially from Facebook discussions that people across the globe wanting to know about their "Blastocystis status" are worried that they are receiving false-negative results from their stool tests, and that many Blastocystis infections go unnoticed. And I think I should maybe try and say a few things on this (please also see a recent blog post on diagnosis, - you'll find it here). I might try and simplify things a bit in order not to make the post too long.

Below, you'll find a tentative representation of the life cycle of Blastocystis. It is taken from CDC, from the otherwise quite useful website DPDx - Laboratory Identification of Parasites of Public Health Concern.

I don't know how useful it is, but what's important here is the fact that we accidentally ingest cysts of Blastocystis, and we shed cysts that can be passed on to other hosts. The cyst stage is the transmissible stage, and the way the parasite can survive outside the body; we don't know for how long cysts can survive and remain infective. In our intestine and triggered by various stimuli, the cysts excyst, transiting to the non-cyst form, which could be called the trophozoite / "troph" stage, or to use a Blastocystis-specific term, the "vacuolar stage" (many stages have been described for Blastocystis, but I might want to save that for later!). This is possibly the stage in the life cycle where the parasite settles, thrives, multiplies, etc. You can see a picture of vacuolar stages in this blog post. Many protozoa follow this simple life cycle pattern, among them Giardia and most species of Entamoeba. If the stool is diarrhoeic and you are infected by any one or more of these parasites, it may be so that only trophozoites, and, importantly, no cysts, are shed! This has something to do with reduced intestinal transit time and, maybe more importantly, the failure of the colon to resorb water from the stool which means that the trophozoites do not get the usual encystation stimuli. Importantly, trophozoites are in general non-infectious.

There is documentation that once colonised with Blastocystis, you may well carry it with you for years on end, and as already mentioned a couple of times, no single drug or no particular diet appears to be capable of eradicating Blastocystis - this is supported by the notion that Blastocystis prevalence seems to be increasing by age, although spontaneous resolution may not be uncommon, - we don't know much about this. Now, although day-to-day variation in the shedding of Blastocystis has been described, it is my general impression that colonised individuals may shed the parasite with each stool passage, and well-trained lab technicians/parasitologists will be able to pick up Blastocystis in a direct smear (both cysts and trophs may be seen). To do a direct smear you simply just mix a very small portion of the stool with saline or PBS on a slide, put a cover slip over it and do conventional light microscopy at x200 (screening) or x400 (verification). Very light infections may be difficult to detect this way, and if you don't have all the time in the world, a direct smear may not be the first choice.

The "king" of parasitological methods, however, is microscopy of faecal concentrates (Formol Ethyl Acetate Concentration Technique and any variant thereof), which is remarkable in its ability to detect a huge variety of parasites. Especially cysts of protozoa (e.g. Giardia and Entamoeba) and eggs of helminths (e.g. tapeworm, whipworm and roundworm) concentrate well and are identified to genus and species levels based on morphology. The method is not as sensitive as DNA-based methods such as PCR, but as I said, has the advantage of picking up a multitude of parasites and therefore good for screening; PCR methods are targeted towards particular species (types) of parasites. A drawback of the concentration method is that it doesn't allow you to detect trophzoites (i.e. the fragile, non-cystic stage), and, as mentioned, diarrhoeic samples may contain only trophozoites and no cysts...

In many countries it is very common for people to be infected by both protozoa and helminths, and in those countries microscopy of faecal concentrates is a relevant diagnostic choice. In Denmark and many Western European countries, the level of parasitism is higher than might be expected (from a hygiene and food safety point of view) but due to only few parasitic species. Paradoxically, the intestinal parasites that people harbour in this part of the world are parasites that do not concentrate well. They are mainly:

1) Blastocystis

2) Dientamoeba fragilis

3) Pinworm (Enterobius vermicularis)

Only troph stages have been described for Dientamoeba fragilis and it may be transmitted by a vector, such as pinworm (look up paper by Röser et al. in the list below for more information); this mode of transmission is not unprecedented (e.g. Histomonas transmission by Heterakis). Eggs of pinworm may be present in faeces, but a more sensitive method is the tape test.

Now, Blastocystis often disintegrates in the faecal concentration process, and while you might be lucky to pick up the parasite in a faecal concentrate, you shouldn't count on it, and hence the method is not reliable, unless the faecal sample was fixed immediatley after being voided. This is key, and also why fixatives are used for the collection of stool samples in many parts of the world - to enable the detection of fragile stages of parasites. There are many fixatives, e.g. SAF (sodium acetate-acetic formalin), PVA (poly-vinyl alcohol) and even plain formalin will do the trick if it's just a matter of preserving the parasite in the sample. If SAF or PVA is used, this allows you to do permanently stained smears of faecal concentrates, and you will be able to pick up not only cysts of protozoa, but even trophozoites. Trichrome and iron-haematoxylin staining are common methods and are sensitive but very time-consuming and may be related to some health hazards as well due to the use of toxic agents. But this way of detecting parasites is like good craftmanship - it requires a lot of expertise, but then you get to look at fascinating structures with intriguing nuclear and cytoplasmatic diagnostic hallmarks. Truly, morphological diagnosis of parasites is an art form! Notably, samples preserved in such fixatives may be useless for molecular analyses.

At our lab we supplement microscopy of faecal concentrates with DNA-based detection of parasites. For some clinically significant parasites, we do a routine screen by PCR, since this is more sensitive than microscopy of faecal concentrates and because this is a semi-automated analysis that involves only DNA extraction, PCR and test result interpretation, which are all things that can be taught easily. Major drawbacks of diagnostic PCR is that you cannot really distinguish between viable (patent infection) and dead organisms (infection resolving, e.g. due to treatment). This is why, in the case of Blastocystis, you may want to do a stool culture as well (at least in post-treatment situations), since only viable cells will be able to grow, obviously.

Two diagnostic real-time PCR analyses have been published, one using CYBR Green and one using a TaqMan probe.

Now, it certainly differs from lab to lab as to which method is used for Blastocystis detection. Some labs apparently apply thresholds for number of parasites detected per visual field, and only score a sample positive if more than 5 parasites per visual field have been detected. I see no support for choosing a threshold, since 1) we do not know whether any Blastocystis-related symptoms are exacerbated by parasite intensity, 2) the number of parasites detected in a faecal concentrate may depend on so many things which have nothing to do with the observer (fluctuations in shedding for instance), and 3) the pathogenic potential of Blastocystis may very well depend on subtype.

If Blastocystis was formally acknolwedged as a pathogen, like Giardia, standardisation of methods would have happened by now. Meanwhile, we can only advocate for the use of PCR and culture if accurate diagnosis of Blastocystis is warranted, while permanent staining of fixed faecal samples constitutes a very good alternative in situations where PCR is not an option.

I have the impression that some labs do DNA-based detection of microbes, including protozoa, and that a result such as "taxonomy unknown" is not uncommon. I don't know how these labs have designed their molecular assays, and therefore I cannot comment on the diagnostic quality and relevance of those tests... it also depends on whether labs do any additional testing as well, such as the more traditional parasitological tests. However, we do know that there is a lot of organisms in our intestine, for which no data are available in GenBank, which is why it is sometimes impossible to assign a name to e.g. non-human eukaryotic DNA amplified from a stool sample.

* More than 1 billion people may harbour Blastocystis.

* Blastocystis is found mainly in the large intestine.

* 95% of humans colonised by Blastocystis have one of the following subtypes: ST1, ST2, ST3, ST4.

* DNA-based detection combined with culture ensures accurate detection of Blastocystis in stool samples and enables subtyping and viability assessment.

Further reading:

Poirier

P, Wawrzyniak I, Albert A, El Alaoui H, Delbac F, & Livrelli V

(2011). Development and evaluation of a real-time PCR assay for

detection and quantification of blastocystis parasites in human stool

samples: prospective study of patients with hematological malignancies. Journal of clinical microbiology, 49 (3), 975-83 PMID: 21177897Below, you'll find a tentative representation of the life cycle of Blastocystis. It is taken from CDC, from the otherwise quite useful website DPDx - Laboratory Identification of Parasites of Public Health Concern.

|

| Proposed life cycle of Blastocystis. |

There is documentation that once colonised with Blastocystis, you may well carry it with you for years on end, and as already mentioned a couple of times, no single drug or no particular diet appears to be capable of eradicating Blastocystis - this is supported by the notion that Blastocystis prevalence seems to be increasing by age, although spontaneous resolution may not be uncommon, - we don't know much about this. Now, although day-to-day variation in the shedding of Blastocystis has been described, it is my general impression that colonised individuals may shed the parasite with each stool passage, and well-trained lab technicians/parasitologists will be able to pick up Blastocystis in a direct smear (both cysts and trophs may be seen). To do a direct smear you simply just mix a very small portion of the stool with saline or PBS on a slide, put a cover slip over it and do conventional light microscopy at x200 (screening) or x400 (verification). Very light infections may be difficult to detect this way, and if you don't have all the time in the world, a direct smear may not be the first choice.

The "king" of parasitological methods, however, is microscopy of faecal concentrates (Formol Ethyl Acetate Concentration Technique and any variant thereof), which is remarkable in its ability to detect a huge variety of parasites. Especially cysts of protozoa (e.g. Giardia and Entamoeba) and eggs of helminths (e.g. tapeworm, whipworm and roundworm) concentrate well and are identified to genus and species levels based on morphology. The method is not as sensitive as DNA-based methods such as PCR, but as I said, has the advantage of picking up a multitude of parasites and therefore good for screening; PCR methods are targeted towards particular species (types) of parasites. A drawback of the concentration method is that it doesn't allow you to detect trophzoites (i.e. the fragile, non-cystic stage), and, as mentioned, diarrhoeic samples may contain only trophozoites and no cysts...

In many countries it is very common for people to be infected by both protozoa and helminths, and in those countries microscopy of faecal concentrates is a relevant diagnostic choice. In Denmark and many Western European countries, the level of parasitism is higher than might be expected (from a hygiene and food safety point of view) but due to only few parasitic species. Paradoxically, the intestinal parasites that people harbour in this part of the world are parasites that do not concentrate well. They are mainly:

1) Blastocystis

2) Dientamoeba fragilis

3) Pinworm (Enterobius vermicularis)

Only troph stages have been described for Dientamoeba fragilis and it may be transmitted by a vector, such as pinworm (look up paper by Röser et al. in the list below for more information); this mode of transmission is not unprecedented (e.g. Histomonas transmission by Heterakis). Eggs of pinworm may be present in faeces, but a more sensitive method is the tape test.

Now, Blastocystis often disintegrates in the faecal concentration process, and while you might be lucky to pick up the parasite in a faecal concentrate, you shouldn't count on it, and hence the method is not reliable, unless the faecal sample was fixed immediatley after being voided. This is key, and also why fixatives are used for the collection of stool samples in many parts of the world - to enable the detection of fragile stages of parasites. There are many fixatives, e.g. SAF (sodium acetate-acetic formalin), PVA (poly-vinyl alcohol) and even plain formalin will do the trick if it's just a matter of preserving the parasite in the sample. If SAF or PVA is used, this allows you to do permanently stained smears of faecal concentrates, and you will be able to pick up not only cysts of protozoa, but even trophozoites. Trichrome and iron-haematoxylin staining are common methods and are sensitive but very time-consuming and may be related to some health hazards as well due to the use of toxic agents. But this way of detecting parasites is like good craftmanship - it requires a lot of expertise, but then you get to look at fascinating structures with intriguing nuclear and cytoplasmatic diagnostic hallmarks. Truly, morphological diagnosis of parasites is an art form! Notably, samples preserved in such fixatives may be useless for molecular analyses.

|

| Iron-haematoxylin stain of trophozoites of Entamoeba coli (note the "dirty" cytoplasm characteristic of E. coli). Source: http://www.atlas-protozoa.com |

At our lab we supplement microscopy of faecal concentrates with DNA-based detection of parasites. For some clinically significant parasites, we do a routine screen by PCR, since this is more sensitive than microscopy of faecal concentrates and because this is a semi-automated analysis that involves only DNA extraction, PCR and test result interpretation, which are all things that can be taught easily. Major drawbacks of diagnostic PCR is that you cannot really distinguish between viable (patent infection) and dead organisms (infection resolving, e.g. due to treatment). This is why, in the case of Blastocystis, you may want to do a stool culture as well (at least in post-treatment situations), since only viable cells will be able to grow, obviously.

Two diagnostic real-time PCR analyses have been published, one using CYBR Green and one using a TaqMan probe.

Now, it certainly differs from lab to lab as to which method is used for Blastocystis detection. Some labs apparently apply thresholds for number of parasites detected per visual field, and only score a sample positive if more than 5 parasites per visual field have been detected. I see no support for choosing a threshold, since 1) we do not know whether any Blastocystis-related symptoms are exacerbated by parasite intensity, 2) the number of parasites detected in a faecal concentrate may depend on so many things which have nothing to do with the observer (fluctuations in shedding for instance), and 3) the pathogenic potential of Blastocystis may very well depend on subtype.

If Blastocystis was formally acknolwedged as a pathogen, like Giardia, standardisation of methods would have happened by now. Meanwhile, we can only advocate for the use of PCR and culture if accurate diagnosis of Blastocystis is warranted, while permanent staining of fixed faecal samples constitutes a very good alternative in situations where PCR is not an option.

I have the impression that some labs do DNA-based detection of microbes, including protozoa, and that a result such as "taxonomy unknown" is not uncommon. I don't know how these labs have designed their molecular assays, and therefore I cannot comment on the diagnostic quality and relevance of those tests... it also depends on whether labs do any additional testing as well, such as the more traditional parasitological tests. However, we do know that there is a lot of organisms in our intestine, for which no data are available in GenBank, which is why it is sometimes impossible to assign a name to e.g. non-human eukaryotic DNA amplified from a stool sample.

* More than 1 billion people may harbour Blastocystis.

* Blastocystis is found mainly in the large intestine.

* 95% of humans colonised by Blastocystis have one of the following subtypes: ST1, ST2, ST3, ST4.

* DNA-based detection combined with culture ensures accurate detection of Blastocystis in stool samples and enables subtyping and viability assessment.

Further reading:

Röser D, Nejsum P, Carlsgart AJ, Nielsen HV, & Stensvold CR (2013). DNA of Dientamoeba fragilis detected within surface-sterilized eggs of Enterobius vermicularis. Experimental parasitology, 133 (1), 57-61 PMID: 23116599

Scanlan PD, & Marchesi JR (2008). Micro-eukaryotic diversity of the human distal gut microbiota: qualitative assessment using culture-dependent and -independent analysis of faeces. The ISME journal, 2 (12), 1183-93 PMID: 18670396

Stensvold CR, Ahmed UN, Andersen LO, & Nielsen HV (2012). Development and Evaluation of a Genus-Specific, Probe-Based, Internal-Process-Controlled Real-Time PCR Assay for Sensitive and Specific Detection of Blastocystis spp. Journal of clinical microbiology, 50 (6), 1847-51 PMID: 22422846

Sunday, May 20, 2012

Brave New World

Using Blastocystis as an example, we have only recently realised the fact that conventional diagnostic methods in many cases fail to detect Blastocystis in faecal samples, which is why we have started using molecular diagnostics for Blastocystis. I was also surprised to realise that apparently no single drug can be used to treat Blastocystis, and that in fact we do not know which combo of drugs will actually consistently eradicate Blastocystis (Stensvold et al., 2010).

There will come a time - and it will be soon - where it will be common to use data from genome sequencing of pathogenic micro-organisms to identify unique signatures suitable for molecular diagnostic assays and to predict suitable targets (proteins) for chemotherapeutic intervention; in fact this is already happening (Hung et al., in press). However, despite already harvesting the fruits of recent technological advances, we will have to bear in mind that the genetic diversity seen within groups of micro-organisms infecting humans may be quite extensive. This of course will hugely impact our ablility to detect these organisms by nucleic acid-based techniques. For many of the micro-eukaryotic organisms which are common parasites of our guts, we still have only very little data available. For Blastocystis, data is building up in GenBank and at the Blastocystis Sequence Typing Databases, but for other parasites such as e.g. some Entamoeba species, Endolimax and Iodamoeba, we have very little data available. We only recently managed to sequence the small subunit ribosomal RNA gene of Iodamoeba, and we demonstrated tremendous genetic variation within the genus; it is now clear that Iodamoeba in humans comprises a species complex rather than "just" Iodamoeba bütschlii (Stensvold et al, 2012).

Ribosomal RNA is present in all living cells and is the RNA component of the ribosome. We often use this gene for infering phylogenetic relationships, i.e. explaining how closely or distantly related one organism is to another. This again assists us in hypothesising on transmission patterns, pathogenicity, evolution, drug susceptibility and other things. Since ribosomal RNA gene data are available for most known parasites, we often base our molecular diagnostics on such data. However, the specificity and sensitivity of our molecular diagnostic assays such as real-time PCRs are of course always limited by the data available at a given point in time (Stensvold et al., 2011). Therefore substantial sampling from many parts of the world is warranted in order to increase the amount of data available for analysis. In terms of intestinal micro-eukaryotes, we have only seen the beginning. It's great to know data are currently builiding up for Blastocystis from many parts of the world, - recently also from South America (Malheiros et al., 2012) - but the genetic diversity and host specificity of many micro-eukaryotes are still to be explored. It may be somewhat tricky to obtain information, since conventional PCR and sequencing offer significant challenges in terms of obtaining sequence data; such challenges can potentially be solved by metagnomic approaches - today's high throughput take on cloning; however, although the current next generation sequencing technology hype makes us feel that we are almost there, it seems we still have a long way to go - extensive sampling is key!

Cited literature:

Hung, G., Nagamine, K., Li, B., & Lo, S. (2012). Identification of DNA Signatures Suitable for Developing into Real-Time PCR assays by Whole Genome Sequence Approaches: Using Streptococcus pyogenes as a pilot study Journal of Clinical Microbiology DOI: 10.1128/JCM.01155-12There will come a time - and it will be soon - where it will be common to use data from genome sequencing of pathogenic micro-organisms to identify unique signatures suitable for molecular diagnostic assays and to predict suitable targets (proteins) for chemotherapeutic intervention; in fact this is already happening (Hung et al., in press). However, despite already harvesting the fruits of recent technological advances, we will have to bear in mind that the genetic diversity seen within groups of micro-organisms infecting humans may be quite extensive. This of course will hugely impact our ablility to detect these organisms by nucleic acid-based techniques. For many of the micro-eukaryotic organisms which are common parasites of our guts, we still have only very little data available. For Blastocystis, data is building up in GenBank and at the Blastocystis Sequence Typing Databases, but for other parasites such as e.g. some Entamoeba species, Endolimax and Iodamoeba, we have very little data available. We only recently managed to sequence the small subunit ribosomal RNA gene of Iodamoeba, and we demonstrated tremendous genetic variation within the genus; it is now clear that Iodamoeba in humans comprises a species complex rather than "just" Iodamoeba bütschlii (Stensvold et al, 2012).

|

| Cysts of Iodamoeba |

Cited literature:

Malheiros AF, Stensvold CR, Clark CG, Braga GB, & Shaw JJ (2011). Short report: Molecular characterization of Blastocystis obtained from members of the indigenous Tapirapé ethnic group from the Brazilian Amazon region, Brazil. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene, 85 (6), 1050-3 PMID: 22144442

Stensvold, C., Lebbad, M., & Clark, C. (2011). Last of the Human Protists: The Phylogeny and Genetic Diversity of Iodamoeba Molecular Biology and Evolution, 29 (1), 39-42 DOI: 10.1093/molbev/msr238

Stensvold, C., Lebbad, M., & Verweij, J. (2011). The impact of genetic diversity in protozoa on molecular diagnostics Trends in Parasitology, 27 (2), 53-58 DOI: 10.1016/j.pt.2010.11.005

Stensvold, C., Smith, H., Nagel, R., Olsen, K., & Traub, R. (2010). Eradication of Blastocystis Carriage With Antimicrobials: Reality or Delusion? Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, 44 (2), 85-90 DOI: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181bb86ba

Friday, May 18, 2012

Blastocystis network on Facebook

This blog includes everything from updates on Blastocystis research, paper evaluations, polls, links, lab SOPs, to network opportunities and social interaction suggestions for all of us interested in Blastocystis. This time I want to guide your attention towards the Blastocystis network on Facebook. This is a good place to discuss personal experience with e.g. Blastocystis diagnosis and treatment and symptoms. The group is called "Blastocystis sp. (Blastocystis hominis and sp.)". If you have any experience and comments on Flagyl/Protostat (metronidazole), CDD regimens, including Secnidazole, Nitazoxanide, Furazolidone, Septrim (or Bactrim), Diloxanide Furoate, or other agents, please look up the group and share... We need your experience and views.

Monday, April 23, 2012

Intestinal Symptoms

For over a century, the clinical significance of Blastocystis has puzzled medical doctors scientists. After realising the extensive genetic diversity in Blastocystis, one of the current main hypotheses is that Blastocystis subtypes differ in terms of clinical significance. In other words: Symptoms, such as diarrhoea or other intestinal upset, may be associated only with one or more subtypes, while other subtypes are strict commensals.

Blastocystis is very difficult to eradicate and colonisation is chronic. Do symptoms caused by potentially pathogenic subtypes persist or do they develop initially only to diminish after host immunological adaptation? Do fluctuations in symptoms reflect fluctuations in parasite load? Such issues ire important when interpreting results generated from cross-sectional surveys of subtypes in various cohorts.

Moreover, intestinal symptoms are difficult to define. Diarrhoea may be defined by 3 stool passages per day or more, while many other symptoms can be very difficult to define, if at all possible. Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and - to some extent - food allergy may both be considered differential diagnoses of symptomatic Blastocystis infections.

IBS diagnosis is currently defined by the Rome III criteria, and there are at least three types of IBS, namely IBS with diarrhoea, IBS with constipation and IBS with a mixture of diarrhoea and constipation.

Symptoms may be experienced differently from person to person. While abdominal cramping is perceived mostly as a symptom and something unpleasant, flatulence may by many be seen as a sign of a "healthy tummy" (e.g. due to consumption of a high fibre diet), although "inconvenient". Some individuals may very well tolerate intermittent intestinal symptoms and do not consult their GPs or other health care professionals, while others may be much more sensitive to any changes in for instance stool patterns.

What some people do not realise is that many methods fail to detect Blastocystis. PCR and culture are the most sensitive methods, but are still only rarely used. Moreover, PCR is also suitable for the detection of Dientamoeba fragilis, which is a parasite often seen in co-infection with Blastocystis. These two parasites are probably the most common single-celled eukaryotes in the human intestine.

This means that complete and accurate microbiological make-ups are far from always performed. And so, incomplete microbiological examination coupled with differential diagnostic challenges, potential immunological adaptation and the very subjective components of symptom presentation renders our quest for clear-cut associations extremely challenging. Blastocystis will often be seen as the culprit of symptoms, possibly simply to the reason that it is the only potential microbial pathogen that has been demonstrated in a stool sample. Cohort studies using sensitive diagnostic methods for pathogen surveillance are expensive, but may be one of the few only ways forward with regard to epidemiological studies that can assist us in resolving the clinical significance of Blastocystis.

Blastocystis is very difficult to eradicate and colonisation is chronic. Do symptoms caused by potentially pathogenic subtypes persist or do they develop initially only to diminish after host immunological adaptation? Do fluctuations in symptoms reflect fluctuations in parasite load? Such issues ire important when interpreting results generated from cross-sectional surveys of subtypes in various cohorts.

Moreover, intestinal symptoms are difficult to define. Diarrhoea may be defined by 3 stool passages per day or more, while many other symptoms can be very difficult to define, if at all possible. Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and - to some extent - food allergy may both be considered differential diagnoses of symptomatic Blastocystis infections.

IBS diagnosis is currently defined by the Rome III criteria, and there are at least three types of IBS, namely IBS with diarrhoea, IBS with constipation and IBS with a mixture of diarrhoea and constipation.

Symptoms may be experienced differently from person to person. While abdominal cramping is perceived mostly as a symptom and something unpleasant, flatulence may by many be seen as a sign of a "healthy tummy" (e.g. due to consumption of a high fibre diet), although "inconvenient". Some individuals may very well tolerate intermittent intestinal symptoms and do not consult their GPs or other health care professionals, while others may be much more sensitive to any changes in for instance stool patterns.

What some people do not realise is that many methods fail to detect Blastocystis. PCR and culture are the most sensitive methods, but are still only rarely used. Moreover, PCR is also suitable for the detection of Dientamoeba fragilis, which is a parasite often seen in co-infection with Blastocystis. These two parasites are probably the most common single-celled eukaryotes in the human intestine.

This means that complete and accurate microbiological make-ups are far from always performed. And so, incomplete microbiological examination coupled with differential diagnostic challenges, potential immunological adaptation and the very subjective components of symptom presentation renders our quest for clear-cut associations extremely challenging. Blastocystis will often be seen as the culprit of symptoms, possibly simply to the reason that it is the only potential microbial pathogen that has been demonstrated in a stool sample. Cohort studies using sensitive diagnostic methods for pathogen surveillance are expensive, but may be one of the few only ways forward with regard to epidemiological studies that can assist us in resolving the clinical significance of Blastocystis.

Wednesday, April 18, 2012

Blastocystis Subtyping in Routine Microbiology Labs

When I speak to colleagues in and outside Europe and visit research portals and social media, including Facebook groups, I get the impression that Blastocystis subtyping is something that is still very rarely done, despite the fact that most clinical microbiologists and biologists acknowledge that subtypes may differ in terms of clinical significance and in other respects. We get new data on Blastocystis subtypes in various cohorts from time to time from research groups around the world, but all reports are characterised by relatively small sample sizes and subtyping methodology has not yet been standardised. This type of research is moreover challenged by the fact that Blastocystis is common in healthy individuals (i.e. people not seeing their GPs for gastrointestinal problems), and this makes it extremely difficult to identify the subtype distribution in the "background" population.

Although we recommend barcoding (see one of my previous posts) as the subtyping method of choice, there is no "official report" identifying the Blastocystis subtyping gold standard. Therefore, I'm currently setting up a lab project that is going to help us compare the most common methods used for subtyping in order to identify the one most suitable. I emphasise that the best method used for subtyping is not the PCR that should be used for diagnostic purposes, mostly due to the fact that PCRs for subtyping amplify 300-600 bp, which are much longer amplicons than the one we go for in diagnostic PCRs (typically 80-100 bp). We therefore recommend our novel TaqMan-based real-time PCR for initial diagnosis, or culture, which is inexpensive and relatively easy and provides you with a good source of cells for DNA extraction.

I hope that we will be able to come up with some robust data soon that will allow us to recommend the most suitable approach and hope to publish our results in a clinical microbiology journal of high impact, and I hope that this will prompt Blastocystis subtyping in many labs. Once this report has been published, I intend to upload a protocol here at the site where lab procedures for diagnosis and subtyping will be described in detail. Stay tuned!

Although we recommend barcoding (see one of my previous posts) as the subtyping method of choice, there is no "official report" identifying the Blastocystis subtyping gold standard. Therefore, I'm currently setting up a lab project that is going to help us compare the most common methods used for subtyping in order to identify the one most suitable. I emphasise that the best method used for subtyping is not the PCR that should be used for diagnostic purposes, mostly due to the fact that PCRs for subtyping amplify 300-600 bp, which are much longer amplicons than the one we go for in diagnostic PCRs (typically 80-100 bp). We therefore recommend our novel TaqMan-based real-time PCR for initial diagnosis, or culture, which is inexpensive and relatively easy and provides you with a good source of cells for DNA extraction.

I hope that we will be able to come up with some robust data soon that will allow us to recommend the most suitable approach and hope to publish our results in a clinical microbiology journal of high impact, and I hope that this will prompt Blastocystis subtyping in many labs. Once this report has been published, I intend to upload a protocol here at the site where lab procedures for diagnosis and subtyping will be described in detail. Stay tuned!

Sunday, April 8, 2012

A Few Words On Blastocystis Morphology and Diagnosis

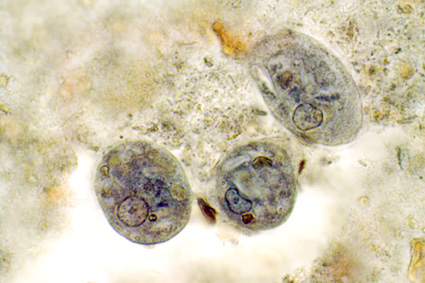

Blastocystis is a sinlge-celled parasite. The parasite produces cysts (probably the transmissible form) and vegetative stages (including the stage commonly referred to as the vacuolar stage). Vegetative stages are commonly seen in fresh faecal samples and in culture. This is what they look like under light microscopy:

Using permanent staining of fixed faecal material, the eccentrically located nuclei become more apparent:

Although sensitive, permanent staining techniques (e.g. Trichrome, Giemsa and Iron Haematoxylin) are relatively time-consuming, impractical and expensive. Since also conventional concentration of unfixed stool using e.g. the Formol Ethyl-Acetate Concentration Technique is not appropriate for diagnosis (Blastocystis cysts are very difficult to pick up, and vacuolar stages become distorted or disintegrate), we recommend short-term in-vitro culture (using Jones' or Robinson's medium) and/or Real-Time-PCR on genomic DNAs extracted directly from faeces using QIAGEN Stool Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) or - in modern laboratories - by automated DNA extraction robots. Once genomic DNAs have been extracted and screened by PCR, positive samples can be submitted to subtyping using the barcoding method, and DNAs can be screened for other parasites by PCR as well. In fact the use of insensitive methods to distinguish carriers from non-carriers is one of our greatest obstacles to obtaining valid prevalence data on Blastocystis.

Having an isolate in culture adds the benefit of having a continuous source of DNA for further genetic characterisation (for instance complete SSU-rDNA sequencing) in case a particular isolate turns out to be genetically different from those already present in GenBank or the isolate database at Blastocystis Sequence Typing Home Page. And chances are that there are quite a few "novel" subtypes out there... especially in animals. However, Blastocystis from animals may not always be successfully established in culture.

| |||

| Vegetative stages of Blastocystis (unstained) (source: www.dpd.cdc.gov) |

Using permanent staining of fixed faecal material, the eccentrically located nuclei become more apparent:

| ||

| Vegegtative stages of Blastocystis (Trichrome stain) (source: www.dpd.cdc.gov) |

Although sensitive, permanent staining techniques (e.g. Trichrome, Giemsa and Iron Haematoxylin) are relatively time-consuming, impractical and expensive. Since also conventional concentration of unfixed stool using e.g. the Formol Ethyl-Acetate Concentration Technique is not appropriate for diagnosis (Blastocystis cysts are very difficult to pick up, and vacuolar stages become distorted or disintegrate), we recommend short-term in-vitro culture (using Jones' or Robinson's medium) and/or Real-Time-PCR on genomic DNAs extracted directly from faeces using QIAGEN Stool Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) or - in modern laboratories - by automated DNA extraction robots. Once genomic DNAs have been extracted and screened by PCR, positive samples can be submitted to subtyping using the barcoding method, and DNAs can be screened for other parasites by PCR as well. In fact the use of insensitive methods to distinguish carriers from non-carriers is one of our greatest obstacles to obtaining valid prevalence data on Blastocystis.

Having an isolate in culture adds the benefit of having a continuous source of DNA for further genetic characterisation (for instance complete SSU-rDNA sequencing) in case a particular isolate turns out to be genetically different from those already present in GenBank or the isolate database at Blastocystis Sequence Typing Home Page. And chances are that there are quite a few "novel" subtypes out there... especially in animals. However, Blastocystis from animals may not always be successfully established in culture.

Thursday, March 29, 2012

Novel Blastocystis real-time PCR

Our new real-time PCR for Blastocystis has been published in JCM.

Check it out at

Development and evaluation of a genus-specific, probe-based, internal process controlled real-time PCR assay for sensitive and specific detection of Blastocystis.

or

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22422846

and use it!

Check it out at

Development and evaluation of a genus-specific, probe-based, internal process controlled real-time PCR assay for sensitive and specific detection of Blastocystis.

or

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22422846

and use it!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)